WE HAVE MOVED!!!

Posted on: November 8, 2008

WWW.MEDAHOLIC.COM

Thanks for reading. The new site will have much more content and features.

Site Move

Posted on: October 31, 2008

I have registered a new domain name. This blog will no longer be open source medicine, though the idea will still remain. It should take 2-3 days to get all my posts moved over to the new site. It should be exciting. But first, I have a midterm to study for. Thanks everyone for all the support so far, I promise I won’t disappoint.

Rehauling the Site

Posted on: October 18, 2008

- In: Thoughts

- 3 Comments

I’m going to take a small break in writing to redo / redesign this blog. Here’s a general outline of things to do.

- Get a Domain Name + Hosting – There’s just not enough control and personalization using a wordpress hosted site. I will be looking to buy a domain name and get some hosting done within the next month, which leads me to my second point…

- Change Blog Name – This is something I don’t want to do, but is inevitable. One reason being opensourcemd.com is already taken but more importantly, I want a site name that really captures the spirit of collaborative health care. Something that really highlights Medicine 2.0. Also, opensourcemd is just too long of a name to be memorable. Hopefully, I can think of something that is under 8 letters long. Any suggestions / ideas would be greatly appreciated.

- Design the Site – What kind of layout do I want, what features should I include, how can I make this user friendly. Unfortunately, this will require me to brush up on my rust html, css, javascript and learn some new skills too. But just like any other job, if you’re not learning and constantly improving yourself and your skillset, you’re going to be left behind.

- Define a Direction – There are tons of medical blogs out there, many of them chronicling the journey through medical school. I don’t want this blog to be just about a personal journal to record stuff, though I do intend to write some personal posts. I want to create more in-depth timeless articles that people will derive real value from. Whether you are a pre-med student, a med student or just the general public, I want you to find the content useful and applicable to you. So over the next month, I will be shaping my vision and direction for this blog.

- Get Ideas – This is similar to point 3. I will be planning out what type of content I want to write about, what niche and audience I will be writing for. The workload is picking up at school and I want to be efficient with my time. By coming up with 25+ ideas / drafts of articles, I can be more productive with my work.

That’s the general gist of things to come. I’ll probably spend a good portion of that time thinking up 2 and 3. A good domain name can go a long way. It should be memorable, clever, short and descriptive of this site. Thanks for reading so far, whether you’re a returning user or somebody who stumbled upon this blog, thank you. Your viewership matters to me and it inspires me to write.

I’ve just finished writing and passing my first medical school exam and though the material wasn’t overly difficult, I’m glad it’s done with. A pass is a pass. Now on to more interesting topics and hopefully more relevant topics. Anyways, it’s safe to say that the honeymoon period of medical school is officially over. No more saying medical school is a “walk in the park” or a “breeze.” The sheer amount of memorization and volume of information is beginning to hit and it doesn’t seem like it’s going to be stopping anytime soon, if ever.

At first, I was quite skeptical of the pass/fail system. The common saying is “What do you call a student who graduates at the bottom of their medical class?” The Answer: “A Doctor!” I initially believed that this whole pass/fail grading system would breed complacency and mediocrity, and I actually felt quite unmotivated for the first exam because of this. Why would I want a surgeon that only answered 75% of the questions correctly in medical school? But I’m finding that’s not the case with me and my classmates. The types of people that make it into medicine aren’t just motivated by extrinsic rewards like academic marks. We like to learn, tackle challenging problems and push ourselves. The more interesting the materials covered in class, they more inclined we are to study.

The pass/fail system ultimately is a good thing for medical students. It reduces cutthroat competition (backstabbing) in the class, unnecessary stress and reduces an examsmanship approach to learning, where people study with only the purpose to maximize their number of points in the game of exams. It creates a partnership of trust between students and teachers where they share the common goal of providing quality education. There is a stronger cohesion amongst students under the pass/fail grading system and there has been no significant difference found in board scores.

I believe the AMSA sums it up quite nicely when they say, “While a pass/fail system may seem easier at first glance, it is just as rigorous as any other kind of grading method. What is missing is not the challenge but the competition.” Afterall, medical school is hard enough to get into – competition with thousands of other motivated students. “The type of student who makes it to medical school in the first place—a successful, motivated achiever—will learn in any kind of system; will learn despite the system.”

Too Many Smart People

Posted on: October 11, 2008

- In: Medical School | Thoughts

- 2 Comments

My dad often says, “Being smart is not enough; there’s just too many smart people in the world.” Although I’ve had this statement repeated to me uncountable times while growing up, I am finding it to be truer everyday. Often it is the simplest words of advice that take a lifetime to fully understand.

Everyday, I am surrounded by bright minds. Medical students are the cream of the science student crop. They are the high school students who are capable of post-secondary education. They are the students who excel in their university academics, who ace the MCAT and who still have time to pursue extracurricular activities. All medical students have a certain level of “smartness.”

I am amazed at the talent of my classmates. One has run multiple marathons and triathlons. Another has worked for the United Nations. Others have completed their PhD’s and are called doctors already. Watching my classmates assimilate large amounts of information in a short period of time for a test is proof of their gifted abilities. I sometimes feel insecure in medical school amongst all these smart people, like an imposter who slipped through the cracks of the admissions committee into medical school. And compared to the doctors and professors who frequently “pimp” the class with obscure questions, my confidence in my abilities is often shaken up. However, being smart and talented IS NOT everything.

Growing up, I was always curious as to how successful people got to where they were. How do athletes win championships and musicians write bestsellers? This curiosity naturally made the biography books – especially autobiographies – a favorite genre of mine. I read up on the lives of great thinkers, pivotal leaders and famous doctors trying to find a common thread to their success. And to my surprise, being smart was not a crucial element. They all acknowledged that their talents and brains gave them a slight advantage over other people, but much like my father, they also acknowledged that there are also many smart people.

A video I’d like to share is from TED talks on success. (For those who haven’t heard of TED before, go check it out, there are a lot of great lectures to view on just about anything) It sums up nicely what I think is needed – on top of being smart – in order to become a good doctor. Enjoy!

- In: Admissions | Applications | Pre-med

- 1 Comment

It’s always strange to see things from a different perspective. Especially if sitting in front of you is

1 Dean of Medicine

4 Administrative Staff

5 Medical Students

3 Faculty Members

8 Practicing Physicians

1 Dean of Science

Dear Readers, I successfully infiltrated medical school’s mystery black box. I have entered the premed’s jury room. The sorting hat of medical school. Being on the admissions committee will be interesting…

How to Self Study for the MCAT

Posted on: October 6, 2008

- In: MCAT | Pre-med

- 6 Comments

I have moved to www.medaholic.com

The MCAT is a high stakes competition; every taker wants to do their best. A good portion will pay test-prep companies for MCAT courses that will teach them the material and test-taking method in hopes of getting the best score.

When I took the studied and prepared for the MCAT, I didn’t take a prep-course from TPR (The Princeton Review) or Kaplan. I studied on my own and… I did perfectly fine. With the right materials in hand, a proper system and discipline, you can do just as well on the MCAT by yourself.

To Read the Rest of this Post Go to my new site

Democratic Healthcare

Posted on: October 1, 2008

Just a short post, I am currently working on a big article that should be up within the next few days. Today, I read something interesting in the New York Times that reflected this concept of open source medicine and collaborative health care that I have been trying to define.

Patients aren’t learning from Web sites — they’re learning from each other. The shift is nothing less than “the democratization of health care”– The New York Times

They have a whole special edition on decoding our health and how information technology is playing a more and more important role. It’s a worthwhile read. Sorry, I couldn’t come up with anything more original today. Busy day at school, I guess it’s expected.

- In: Medical School | Thoughts

- 2 Comments

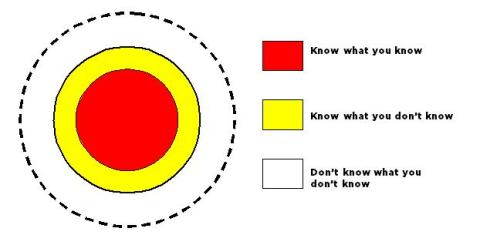

I am doing my problem-based-learning (PBL) background research and this picture popped into my head.

This diagram represents how we view knowledge and applies to any field of subject, not just medicine. As you study any subject more in-depth, you soon realize that you don’t know anything at all. As your knowledge increases, so does your awareness of what you don’t know. I can easily see how a person can devote their entire lives to learning about the kidneys, the brain or even an obscure protein. The knowledge never stops growing. It’s quite a humbling experience.